The Honorable George Bush has rendered a lifetime of extraordinary service to the United States and its citizens. As a highly decorated naval aviator, as a Congressman, as United States Ambassador to the United Nations, as Chief of the United States Liaison Office in Communist China, as Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, as Vice President and ultimately as our 41st President, his continuing selfless contributions in the national interest have exemplified the ideals of West Point, as expressed in its motto, “DUTY, HONOR, COUNTRY.”

George Bush’s service to the nation was born in the crucible of World War II aerial combat. Flying fifty-eight combat missions in the Pacific Theater as a torpedo bomber pilot, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and three Air Medals for his courageous acts of gallantry.

A decade later, he reentered public service, winning election to Congress as Representative of the Seventh District of Texas. During his two terms in office, he staunchly supported United States military intervention in Vietnam, headed the Republican Task Force on the Environment and forged an indelible reputation for political courage with his vigorous support of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, a bill highly unpopular with many of his constituents.

George Bush’s contributions as a diplomat began with his appointment as United States Ambassador to the United Nations, where he led the fight to establish a two-China policy. His efforts uniquely qualified him for his subsequent appointment as Chief of the United States Liaison Office to Communist China, where he played a key role in the re-establishment of full diplomatic relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

In 1975 President Ford appointed George Bush Director of the Central Intelligence Agency. In this post he resurrected a foundering agency, restoring its morale and revitalizing its effectiveness as the leading element of the United States Intelligence Community.

In 1980 George Bush was elected Vice President, continuing his lifelong preparation for the presidency. As Vice President, he headed the Presidential Task Force on Regulatory Relief and led the National Narcotics Border Interdiction System. In 1985 he assumed the leadership of the nation’s comprehensive program to combat international terrorism.

In 1988 George Bush was elected 41st President of the United States. As President, he led the nation into the post cold war era. The sternest test of his national leadership came in 1990, when Iraq invaded Kuwait. As Commander in Chief and as leader of the free world, he forged an international coalition of nations to halt Iraqi aggression in the Middle East. He orchestrated the rapid deployment of US and allied military forces to defend Saudi Arabia. When diplomatic efforts failed to achieve a peaceful withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait, he launched Operation Desert Storm to eject and destroy these forces. Victory was incredibly swift, mercifully low in coalition casualties and resulted in the utter destruction of the offensive capability of the Iraqi Armed Forces. George Bush’s leadership was masterful—clearly the capstone of his Presidency and a standard for his successors to emulate.

George Bush has devoted a lifetime—almost a half century—to the service of his country. His matchless record of achievement personifies uncommon dedication, honesty and patriotism and is in keeping with the finest traditions of American public service. Accordingly, the Association of Graduates of the United States Military Academy hereby presents the 1994 Sylvanus Thayer Award to the Honorable George Bush.

Article

Assembly 1995 Jan. – On Wednesday, 5 October 1994, a day as festive as it was blustery, the Association of Graduates, the United States Military Academy, and the Corps of Cadets welcomed former President George Bush to West Point and bestowed on him the 37th annual Sylvanus Thayer Medal, the Academy’s most prestigious award. It was President Bush’s fifth official visit to West Point and the third time the award has been given to a former President. (Mr. Bush follows Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1961 and Ronald Reagan in 1989).

The award is conferred annually upon an outstanding citizen “whose record of service to their country, accomplishments in the national interest, and manner of achievement exemplify outstanding devotion to the principles expressed in the motto of the United States Military Academy—Duty, Honor, Country.” It is named in honor of Sylvanus Thayer, USMA Class of 1808, the 33d graduate of West Point and its fifth superintendent (1817-1833). Previous awardees have included Douglas MacArthur ’03, Francis Cardinal Spellman, Neil A. Armstrong, Warren E. Burger, and George P. Shultz.

A Reception, a Parade (but no Saber)

President Bush arrived by helicopter at 1430 hours unaccompanied by his wife Barbara (to the mild disappointment of many) the guest of the Superintendent, Lieutenant General Howard D. Graves ’61, and his wife Gracie. Mr. Bush first paid a visit to the Superintendent at his office, then received an official reception at Cullum Hall, where he was greeted by distinguished guests of the Association of Graduates and by prominent members of the greater West Point community.

Just before 1700 hours, following the reception, the former President was escorted to the parade field to be honored with a double regimental review and the presentation of a memento, a fine porcelain statuette of a cadet at attention. The customary gift, a cadet saber, was not given because President Bush received one in 1984, when, as Vice President, he delivered the commencement address. An hour later, President Bush, his party, the Corps of Cadets and numerous guests repaired to Washington Hall for the evening banquet and Thayer Award Ceremony. Among the attendees were BG Freddy McFerrin ’66, Commandant of Cadets, and his wife Aubrey; BG Gerald E. Galloway ’57, Dean of the Academic Board; Mr. John A. Hammack ’49, Vice Chairman of the Association of Graduates, and his wife Gloria; COL (Retired) Seth Hudgins ’64, President of the AOG, and his wife Joy; Mr. Denis Mullane ’52, former President of the AOG, attending with his family; GEN (Ret) Brent Scowcroft ’47, former National Security Advisor; and LTG (Ret) Dave R. Palmer ’56, former Superintendent.

Prior to the reading of the citation and conferring of the award, the former President was introduced by the Superintendent and the Vice Chairman of the AOG, Mr. Hammack. General Graves noted the timeless significance of Colonel Thayer’s insistence on character as an essential element of leadership, and Mr.Hammack lauded the decision of the Selection Committee—made up of a dozen graduates from the Class of January 1943 to the Class of 1980—to nominate George Bush for the award. The citation, written by General (Ret) Edward C. Meyer ’51, Chairman of the AOG, was then read. It touched upon Mr. Bush’s accomplishments as a naval aviator, congressman, ambassador, Director of Central Intelligence, vice president, and, finally, the nation’s 41st President, devoting special praise to President Bush’s leadership in the Gulf War. This leadership, the citation declared, was “a standard for his successors to emulate” and the culmination of “a matchless record of achievement.” After the citation the medal was presented and President Bush began his remarks.

An Unexpected Visit, a Delighted ClassGeorge H. Bush Sr. at West Point 1994

At the end of the evening the former President retired to Quarters 100 and a well-earned rest. The next day began early at the Supe’s, where—for the first time in recent years—the honored guest enjoyed breakfast with a small group of cadets. President Bush surprised his hosts by announcing his wish to visit a class that morning. Caught off guard but delighted, General Graves telephoned Colonel James Golden ’65, head of the Department of Social Sciences, and arrangements were hastily made. As Colonel Golden describes his morning: “The phone rang at 0815. The Superintendent was on the line. I congratulated him on a great ceremony the day before, and he told me that this morning would be even more interesting. President Bush’s departure had been delayed, and he wanted to see a Social Sciences class. They were about to leave Quarters 100 and would be at Lincoln Hall in five minutes. I was relieved to find a course on Legislative Politics in session and asked Major Clemson Turregano (Citadel ’83) if he had ever taught a President before. General Graves and President Bush arrived and the class quickly moved to a question-and-answer session. As usual, the cadets came through with flying colors. One asked, ‘Mr. President, if Congress had not approved the Gulf War resolution, what would you have done?’ We were off and running.”

Perhaps we should not have been so surprised. After all, President Bush had gone out of his way to seek out and talk with cadets throughout his visit and on his previous sojourns at the Academy. In addition to being one of the most impressive of Thayer awardees, George Bush proved himself one of the most personable.

Speech

It is an honor to be at the shrine of “Duty, Honor, Country.” I Tonight, I know what Douglas MacArthur meant by saying, “In the evening of my memory, always I come back to West Point.” For me, we’ll call this the twilight of my life. I am proud to be an honorary member of the Long Gray Line.

I do not miss a lot of things about my past job. I don’t miss the rough and tumble of politics that I once loved. I do not miss dealing with the national press, something I used to enjoy—well, at least at times. But I do miss dealing with our great military. I really do.

For me it is very special to be back at the Point, knowing that—like the Lincoln Memorial, Statue of Liberty, or Pearl Harbor—this ground at West Point reflects what we believe …and what we are.

Sylvanus Thayer was quite a person—soldier, educator, leader. The award presented in his name is bestowed by men and women who made a difference, not because they wished it but because they willed it. Like “The Father of this Academy,” they knew that while liberty was not accidental, the hard work of freedom could make it seem providential.

Tonight’s program lists the honor roll of Thayer recipients. Generals. Ambassadors. Two Presidents. Each knew that principle is worth fighting for, just as country is worth dying for. My generation was charged with winning a war— today’s, with preserving the peace. But our goal is the same: to achieve the lasting peace that stems from planning, patience, and sacrifice. From strength that is moral, economic, and military.

The day I graduated from school in June I942, our country had been at war for 6 months. Secretary of War Stimson gave our commencement speech. He spoke of how the American soldier should be: “brave without being brutal, self-confident without boasting, part of an irresistible might without losing faith in individual liberty.” I didn’t know it then, but he was describing the real peacemakers. To them—to all of you—I wish to dedicate this award.

I’ve been out of office about 2I months now. It’s been a time when I’ve certainly heard a lot. It’s also been a time when I’ve thought a lot—about our kids, their future; about challenges met and problems that remain. And I’ve come to a conclusion: I’m an optimist…provided that America leads.

I know there are many problems abroad: terrorism, proliferation of weapons, ancient ethnic and tribal rivalries resulting now in mortal combat. Yes, there are many problems, but look at the big picture. When I look back, I see the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the liberation of Eastern Europe, the crumbling of the Soviet Union. I see ancient enemies in the Middle East talking with one another, something no one would have dreamt of five years ago. I see an arms control deal I made with Boris Yeltsin and a world made safer through the erasing of ICBM missiles. I see a baby I was proud to father, a baby called “NAFTA,” coming of age under a new President. I see this and know it’s cause for optimism.

I also see that some times some of us lose sight of how far we’ve come. Of course, there are problems now, but recall the horrors seen by recent generations: the Soviets blockading Berlin; the Cuban Missile Crisis bringing us to the brink of nuclear destruction; tanks rolling into Prague; the death toll mounting in Viet Nam. Compare that with today: no more superpower confrontation, a democratic Germany reunified, democracy sweeping the Americas, political and economic reform in Eastern Europe. Our young must not let pessimism blind them to freedom’s light.

Think of the end of the arms race. The collapse of the Iron Curtain. The end of the Cold War. This horizon of a better world began to emerge as the United States and the Soviets ceased to be on opposite sides. One early sign of this was when Gorbachev stood with us against Saddam Hussein. We formed a huge international coalition to stand against aggression. Much of the world stood with us. As Vietnam had diminished it, Desert Storm restored our credibility. Incidentally, in Desert Storm the politicians got out of the way and let the military fight the war to win it. The USA led the way. And the key now is still American leadership, for we are the only superpower. That bequeaths to us a mandate of responsibility; it is our duty and destiny to lead.

I can’t help but reflect on the challenges our country has faced in this century and on the challenges it confronts as we near the 2Ist Century. Perhaps the greatest is to construct a role for America in the post-Cold War world that is both effective and politically sustainable. We have fought in three world wars in this century. World War I, World War II, and the Cold War. We were victorious in all three, but we have not always been as successful in “winning the peace.”

In the wake of World War I, we faced a conflict between Wilsonian idealism and traditional American isolationism. Isolationism prevailed. The U.S. withdrew from international engagement and, in doing so, squandered much of what we had won in the bloody trenches of France.

With courage and sacrifice, and at great cost in blood and treasure, we led the Allied forces to victory in World War II. We then faced a choice. On the one hand, returning to American isolationism; on the other, American leadership of the free world facing a growing Soviet menace. This time—recalling painfully learned lessons and prodded by a belligerent Soviet Union— American internationalism won out, and the seeds were planted for our victory in the Cold War.

We now find ourselves in yet another postwar period, again facing a choice between American isolationism and leadership. The choice we make will affect not only the kind of world in which we live but also American well-being and vitality.

Today, many want us to shed the burdens of international leadership we shouldered during the Cold War. They say: ’’We’ve done our part;” “turn inward;” “slash the defense budget;” “apply the so-called ‘peace dividend’ to our domestic needs and priorities.” A growing chorus urges that we let the outside world take care of itself while we take care of ourselves.

After the I992 election, I consider myself to be uniquely qualified to talk about the seductiveness of isolationism. None of the candidates were challenged during the campaign to articu¬late, much less defend, their vision of America’s role in the emerging post-Cold War world. None were asked about key foreign policy priorities or simply where they stood on key international issues. On the contrary, speaking to these issues became a sort of political liability.

But if the echoes of our post-World War I experience are undeniable, so are its lessons. Like the aftermath of the first World War, the post-Cold War world presents a chance to shape a new international order which better reflects our values and serves our interests. At the same time, it also turned out to be messier and more unstable than we had expected. We face not the end of history but, rather, the march of history. Not the end of ideology but the resurgence of intolerant nationalism, religious fanaticism, and bloody ethnic strife, fueled by the proliferation of deadly weapons and unrestrained terrorism.

It is true that this unstable world may not threaten us directly and immediately. Thus, the temptation to turn our backs on the world and concentrate on “domestic” problems. It is also true that history shows how following neo-isolationism serves neither our values nor our interests. We may be able to postpone a foreign policy day of reckoning, but we cannot avoid it.

The foreign policy I’m referring to is non-partisan and bipartisan. This century has taught Presidents of both parties that the choice between American international leadership and American isolationism is a false choice indeed.

We face only two real choices. We can either seize the W V chance presented by our victory in the Cold War to help shape a new world order, or we can squander that chance by failing to exercise leadership and accept whatever kind of world results. Much as we may wish otherwise, we do not have the option of cutting ourselves off from that world and insulating ourselves from its challenges and problems. And presidents find that, much as we might wish it otherwise, they neither are free to put foreign policy on the back burner nor insulate their domestic policy clout from their foreign policy performance.

These are lessons which each president knows or soon learns. That is, presidents have won elections and assumed office with varying mandates to be either mostly a “foreign policy president” or a “domestic policy president.” What is striking is that every president since World War II—and in many respects each president since World War I —ultimately finds himself needing to devote much time, attention, and political capital to foreign policy issues. What divides them is how well prepared they have been to fill this role, whether they welcomed or resisted it.

The same is likely to be true for post-Cold War presidents for the foreseeable future. As has been true for most of the 20th Century, U.S. leadership is and will remain indispensable to protect our interests and achieve a world order which reflects our values. Our leadership in the post-Cold War world will do much for freedom by being both noble and self-interested.

Let me be clear about what I do and do not mean by American leadership. I do not mean that America should become the world’s policeman. We should not attempt that, and would surely fail if we did. A better metaphor is to regard the U.S. as a “sheriff’ offering to organize and lead the posse against international wrongdoers, but not shouldering the burden alone or defending others’ interests for them.

Instead, we should focus on cases in which: first, important U.S. interests and values are at stake; second, U.S. participation—and especially leadership—could make the critical difference; and, yes, third, where there is a high probability of success. Success not only breeds success but also reduces the chances that U.S. commitments will be tested.

I do not mean that America must be responsible for righting every wrong or confronting each threat to world order. I do mean that if we don’t defend our interests and stand up for what we believe, no one else will. When and where we choose not to lead, no other country or institution is apt to magically appear.

In particular, it is naive to think that the U.S. can successfully evade hard choices simply by calling for the U.N.

Finally, we must accept the reality that, in exercising our post-Cold War world leadership, there is no substitute for credible, effective American power. Yes, military power. The world we face places a premium on military leaders who combine skill, professionalism, instinct, and sound judgment. General Marshall had it right. America’s are “the best damn kids in the world.” We look to you, the men and women of West Point, to give them sterling leadership. We must add a sound defense strategy, a defense budget sufficient to support it, and missions which serve important U.S. interests whose benefits clearly exceed the costs and which have realistic prospects for success.

The leadership I mean has common hallmarks. First, credibility: allies and adversaries must believe that we mean what we say and that we will finish what we start. It is impossible to exaggerate not only the value of U.S. credibility but also its vulnerability to damage when our rhetoric outstrips our capability or our will. I am absolutely convinced that Saddam Hussein never felt we would use the force deployed against him. He watched the demonstrations in front of the White House. He read the editorials warning me against the use of force. He heard the dovish speeches on the Senate floor. “Give peace a chance;” “body bags;” “let sanctions work.” He remembered Viet Nam— where the politicians, not the military, called the shots in that war. In sum, he did not feel we would fight, but, if we did, he felt he could achieve some standoff in the desert. Those who went before you here and hundreds of thousands of other of the “best damn kids in the world” proved him wrong. We whipped him, and, in the process, we restored America’s credibility.

In addition to credible, we must be consistent. Nothing undermines our credibility more than to appear to be in a constant state of flux about our objectives, assurances, strategies, and threats.

The third hallmark of leadership is capability. The end of the Cold War has not produced some huge political and defense “peace dividend.” If we rush to spend what isn’t there, we will waste our ability to defend our interests or exercise leadership.

Fourth, selectivity. We may be the world’s only superpower, but even we must learn how to be selective lest we maim our capacity for leadership.

Let me end where I began. America can again pick up the L baton of leadership and mold a troublesome world into one more compatible with our values. Or we can turn inward. History teaches us that if we do that we will surely, as night follows day, wake up to face a nasty surprise.

We must make the right choice. I pray that we have the wisdom, foresight, and imagination to make that choice America’s instrument of freedom. I believe that the American Revolution is a beginning, never a consummation. We can strike a blow for liberty by choosing to engage and to lead anew.

In the darkest days of the Civil War, Lincoln was asked whether God was on his side. He replied: “The question is not whether God is on our side, but whether we are on God’s side.” It is not too much to say—history records it—that for two centuries West Point has been on honor’s side.

For that, I thank you, and for showing that ours is the land of the free because it is the home of the brave. Thank you for tonight. I am truly grateful for this award. God bless you. And God bless the United States of America.

Biography

George Herbert Walker Bush was born on June 12, 1924, in Milton, Massachusetts. Mr. Bush attended Phillips Academy, in Andover, Massachusetts graduating on his 18th birthday. That

same day, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy. When he received his wings and commission in June 1943, he was still 18 years old and the youngest pilot in the Navy at that time.

During World War II, Mr. Bush flew torpedo bombers off the USS San Jacinto. On September 2, 1944, Mr. Bush’s plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire while making a bombing run over the Bonin Island of Chichi Jima, 600 miles south of Japan. Although the plane was afire and severely damaged, he completed his strafing run on the targeted Japanese installation before flying towards the sea to bail out. For his courageous service in the Pacific Theater, Mr. Bush

was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and three Air Medals.

Following World War II, Mr. Bush entered Yale University, where he pursued a degree in economics and served as captain of the varsity baseball team. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1948. After his graduation, George and Barbara Bush moved to Texas, where he worked as an oil field supply salesman for Dresser Industries. Between 1951 and 1954, he co-founded three successive petroleum companies. The third firm, Zapata Off-Shore, pioneered the development of experimental offshore drilling equipment.

Following an unsuccessful bid for a Senate seat in 1964, Mr. Bush was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966 from Texas’ 7th District. One of the few freshman members of Congress ever selected to serve on the Ways and Means Committee, he was re-elected to the House two years later without opposition.

During the 1970s, Mr. Bush held a number of important leadership positions. In 1971, he was named U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. In 1973, he became Chairman of the Republican National Committee. In October 1974, Mr. Bush was appointed Chief of the U.S. Liaison Office during the critical period when the United States was renewing ties with the People’s Republic of China. In 1976, Mr. Bush was appointed Director of Central Intelligence. He is given credit for strengthening the intelligence community and restoring morale at the CIA while Director.

In 1980, Ronald Reagan selected George Bush to be his running mate. On January 20, 1981, Mr. Bush was sworn in for the first of two terms as Vice President. In that office, Mr. Bush coordinated Administration efforts to combat international terrorism and wage international war on drugs. Vice President Bush also piloted a task force on regulatory relief, aimed at reducing government regulation and increasing American competitiveness.

In 1988, George Bush became his Party’s nominee and the American people’s choice to be the 41st President of the United States. Mr. Bush’s leadership proved critical to the resolution of some of the most daunting conflicts of our time: The fall of the Berlin Wall and reunification of Germany; the end of the Cold War and the flowering of democracy in Eastern Europe; the emergence of a new partnership with Russia, anchored by the historic arms reduction treaties, START I and START II—the first-ever agreements to dismantle and destroy strategic weapons since the advent of the nuclear age.

With the passing of the Cold War came new challenges. In a vivid demonstration of post-Cold War possibilities for collective security, President Bush marshaled a 30-nation coalition to oppose Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. Desert Storm stands as a testament to Presidential leadership—and American resolve in an uncertain and often dangerous world.

On January 6, 1945, George married Barbara Pierce of Rye, New York. Today they are the parents of five children: George, John (Jeb), Neil, Marvin, and Dorothy Bush Koch. Their second child, Robin, died of leukemia in 1953. The Bushes have 13 grandchildren. President and Mrs. Bush reside in Houston, Texas.

Additional Information

Local News Article

Reprint of Middletown Record Article by Ed Shannon dtd 6 OCT 94

President at Academy for award

West Point – Former President George Bush came to the U.S. Military Academy last night to pick up the Thayer Award and used the visit to warn the United States against turning its back on the rest of the world.

Noting that “many want us to shed the burden of leadership we shouldered during the Cold War,” Bush said such a move would surely come back to haunt the country.

“We may be able to postpone a foreign policy day of reckoning, but we cannot avoid it,” Bush said. His remarks came during a 25-minute speech to a packed Washington Hall crowd that included the Academy’s 4,200-member Corps of Cadets and about 300 guests.

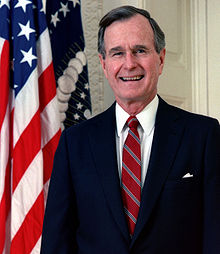

Looking trim in a crisp blue suit, the 70-year-old Bush also cautioned against using the end of the Cold War as an excuse for slashing the country’s military budget. The call drew appreciative nods from the crowd of past, present and future Army officers.

“If we don’t defend our interests and stand up for what we believe, no one else will,” the former Navy fighter pilot said. “Where we choose not to lead, no other country or institution is apt to magically appear.”

Bush stressed that he did not believe the United States should be the world’s “policeman,” but more like a “sheriff” to “organize the posse, but not shoulder the burden ourselves.”

He pointed to his own success in the Persian Gulf War as an example of how the United States can lead other nations against a hostile enemy.

And – in what sounded like a muted criticism of his successor, President Clinton – Bush said the country’s image as the last true superpower will suffer from an indecisive foreign policy.

“Nothing undermines our credibility more than to be in flux,” he said.

As for his forced retirement from public life, Bush said there was little that he missed.

“I darned sure don’t miss the rough and tumble of politics that I used to thrive on,” he said before launching into a line that drew loud applause from the crowd. “I don’t miss dealing with the national press, That has got to be the understatement of the year.”

In receiving the Thayer Award, Bush became the third former President to be so honored; Dwight D. Eisenhower and Ronald Reagan also got the award. Other honorees have included GEN Omar Bradley, evangelist Billy Graham and comedian Bob Hope.

The award – named for Sylvanus Thayer – has been given by West Point graduates every year since 1958 to a United States citizen whose accomplishments embody the academy’s motto: “Duty, Honor, Country.”

Thayer is considered the “Father of the Military Academy” because he laid the foundation for the institution’s educational system, placing a special emphasis on engineering sciences.